By Mary Bond

Originally published in Massage & Bodywork magazine, June/July 2007.

As the concept of holism gains acceptance in Western culture, it becomes increasingly commonplace to find ourselves impressed by the ways in which everything is connected to everything else. We embrace holism in our approaches to health. We pray for our leaders to embrace holistic understanding of our geographical and political environments. We find significance in the synchronous thoughts and events of our personal lives. “There are no accidents,” we say.

But although we acknowledge body and mind as a continuum, we have yet to regard human posture through a holistic lens. Most people still define posture as an ideal position of the chest, shoulders, and neck. This positioning is so idealized that if you mention posture in public, you will observe sheepish adjustments of spines and shoulders into positions that look both stiff and inauthentic.

However, in our hearts, we know posture reflects how we are and how we feel at any given moment. We know posture is complex. If we are down in the dumps, our bodies sag; when our spirits lift, so do our bodies. Therefore, we experience our posture holistically. We know, even if unconsciously, that posture includes the ways in which we move and breathe, digest and think, feel and perceive. So, surely it is time to revise our definition of posture to reflect what we actually feel in our bodies. In a previous issue of Massage & Bodywork, I discussed the importance of including the movements of the pelvis and hips in our understanding of posture and body use.1

In this article, I will share my understanding of the ways in which our breathing habits affect posture. To set the stage, we’ll review some of the anatomy of breathing. Next, we’ll deepen our understanding of posture by observing the way it is determined by our perceptions of the world. To do this, we’ll examine the impact of our perceptions on both respiration and posture. And lastly, we’ll apply our new understanding of posture and breathing to how we use our bodies as we work with clients.

Healthy breathing habits and healthy posture go hand in hand. Yet, people who complain of breathing problems are seldom led to correct a related postural fault, and people who complain of poor posture seldom realize that their faulty breathing is involved.

The Movements of Breathing

Breath is so essential to life that it’s easy to overlook the fact that it involves movement. So, like all other movements, breathing movements can be performed gracefully and efficiently, or poorly and painfully. Our breathing can be shallow or full, labored or free.

The basic movements of breathing are the successive expansion and contraction of the rib cage. The expanding movement—inhalation—creates a vacuum within the lungs that draws the air inside. Exhalation occurs when the rib cage reverses its motion, compressing the interior space of the lungs and forcing air out.

During inhalation, the spine subtly extends, lifting the trunk. This movement also facilitates the subtle pivoting of the ribs at their juncture with the spine. This rotation of the ribs at the costo-vertebral joints provides leverage for elevation of the anterior part of the rib cage. Together, the movements of the spine and ribs expand the rib cage in three dimensions, increasing its interior space. If the spine is so bound by myofascial tension that extension of the spine is restricted, full expansion of the rib cage will also be restricted. Conversely, if the rib cage and chest are stiff, it is next to impossible for the spine to extend the way it should during inhalation.

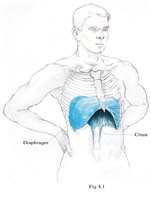

The inhalation movements of the spine and rib cage are coordinated with the contraction of the diaphragm—the primary muscle involved in breathing. Diaphragmatic contraction occurs in two phases. During the initial phase, the peripheral attachments of the muscle are drawn inward toward the central tendon, causing the dome of the muscle to flatten and descend. This creates space within the rib cage for the lungs to expand and air to enter. During this phase, the diaphragm also presses down on the abdominal contents, causing the abdomen to protrude. This is sometimes called abdominal breathing.2

During the diaphragm’s second phase of contraction, downward movement of the dome is blocked by healthy tone in the transversus abdominus muscles. With the central tendon now fixed downward, the further contraction flares the peripheral attachments away from the center. This initiates the expansion of the lower rib cage and allows further lung expansion.

In people whose deep abdominal muscles are underactive, the diaphragmatic initiation of rib cage expansion does not occur, and the rib cage must be expanded by the scalenes and the accessory breathing muscles of the upper chest and shoulders. This leads to chronic tension in these areas, adversely affecting posture. The abdominal muscles can also interfere with lower rib cage expansion if they are overactive. For example, if the posture of the chest is habitually compressed, the external obliques and rectus abdominus attachments to the rib cage will be short and tight. Overemphasis on upper abdominal exercise, such as crunches, can also shorten these attachments. Tightened myofascia of the lower rib cage impedes both the downward and outward motions of the diaphragm, severely limiting inhalation.

The movement of exhalation—the diminution of the rib cage—takes place when the diaphragm relaxes. The diaphragm is the only breathing muscle we engage when we are lying down. When our bodies are thus fully supported by gravity, exhalation is a passive movement of the diaphragm that should involve no sense of effort.

The more upright we are, and the more active we are, the more we must engage the intercostal, posterior serrati, and scalene muscles to help expand the ribs for inhalation and the more we need the bellows-like pumping of the abdominals to assist with exhalation.

Massage and bodywork improve breathing whenever they release tension in the myofascia of the spine, chest, abdomen, neck, or shoulders. You are addressing your clients’ breathing—and, indirectly, their posture—in every session. In doing this, you are freeing their bodies, however temporarily, from their most recent postural tensions and breathing restrictions.

Posture as Perception

The word posture derives from Latin meaning to put or to place. By considering what purpose underlies the putting and placing of our bodies, we will gain insight into the holistic nature of posture.

The very instability of our bodies is what allows them the vast variety of movement displayed on a professional basketball court or on the stage of Cirque du Soleil. The engineering of human bodies, with their rounded joint surfaces and fluid tissues, makes them perfect for movement. But for our movements to achieve their desired ends, we must temporarily immobilize parts of the body to provide leverage for moving other parts. To hit a target with a dart, for example, the legs and trunk must provide a stable enough platform for the throwing arm to move with finesse. We might propose that the purpose of posture is to stabilize our bodies in readiness for purposeful activity.

But there is another activity that occurs before we stabilize our bodies. Our first response to any situation is to determine where we are. Just as stabilization readies us for action, orienting ourselves readies us for stabilization. We locate ourselves in space through perceptual activity so reflexive and unconscious that we seldom realize we are doing it. Our perceptual orientation to any situation is a subtle movement, a “putting” of the body into the best configuration for receiving the information involved. When we hear a sudden, unfamiliar sound, for example, our necks automatically extend, putting our heads into the best position for determining the significance of the sound.3

Similarly, as you prepare to throw a dart, you evaluate your surroundings. If you’re in a bar, for example, your sense of the rowdiness of the crowd helps you gauge the likelihood of someone bumping your throwing arm. The sounds you hear and activity you observe through your peripheral vision help you adjust your stance accordingly. Or, when you’re preparing to give a massage, your perceptions factor in the room’s spaciousness and temperature, your own mood and energy level, and your relationship with the client. These, and a dozen other impressions, influence the way you “put” yourself as you begin the activity. The senses work together to give us the information we need to orient ourselves and stabilize our bodies for action.

While the details of what we perceive are as various as life itself, our orienting perceptions still fall into only two basic categories. First, we locate ourselves through our relationship with gravity by perceiving our bodies in relation to the ground. Second, we orient in space by knowing where we are in relation to our surroundings—to the people, objects, and events in our environment. Environment in this sense includes both physical location and the overlapping personal, social, and energetic spaces that envelop us. Thus, we locate ourselves through our perceptions of ground and space.

Down and Up

To understand what I mean about perceiving ground and space, try the following mental experiment. Recall what it feels like to be on a swing. Close your eyes for a moment and imagine yourself reliving the experience. As children, what was so pleasurable about swinging was the way the body’s changing relationship to gravity made us feel. On the downward plunge, our bodies felt weighted, heavy, and solid. But when the swing’s momentum defied gravity and took us flying, we felt ourselves blended with the air and knew ourselves as creatures of sky and light, weightless and spacious.

These same perceptions, in subtle measure, organize our nervous systems to activate the muscles that produce and maintain upright posture. The perception of down lets our bodies feel grounded, while the perception of space gives our bodies lift.

Gravity gives our bodies weight, and we perceive our weight through our proprioceptive sense. This system of internal feedback is complex and is composed in part of sense receptors located in muscles and joints. We interpret the sensations of muscular relaxation as heaviness, because we sense our body parts are closer to the earth (i.e., down).

When we are emotionally down, our sense of weight can feel exaggerated. We drag ourselves along, every action requiring we hoist the body up from the earth. In such a mood, we have little sense of the spaces that surround us. People, objects, and events seem monotone and dimensionless, and our muscles are difficult to arouse. Our posture and breath are labored.

The capacity to orient ourselves in space takes place through the tactile, visual, auditory, and olfactory senses. We touch, see, hear, and smell our surroundings. The resulting sensations activate the postural muscles to lift the body and hold it away from the earth. There is a natural correspondence between spatial awareness and inhalation. When we inhale, we literally allow outside space inside our bodies. This is reflected in our metaphors for personal space or privacy—we commonly speak of breathing room or breathing space.

Just as our spirits and bodies can be held too far down, they can also soar too high. If we are caught up in ideas and intentions, frantically waiting for results, we barely feel our bodies. We are unable to come down, unable to relax. Our movements tend to be jerky and disconnected. We are light on our feet, but without rest or rhythm.

When our orienting perceptions are balanced between ground and space, the tone in our postural muscles is adaptable, with optimal resting length between their attachments. This span between the proximal and distal attachments is the basis for the most efficient and the most graceful coordination of the body, including our breathing.

Your best posture and freest breathing occurs when you are in a relaxed, good mood. In such moments, your perceptions are open and adaptable. You are aware of the spaciousness of your world and, at the same time, you feel at ease on the planet, secure and grounded. Also at such moments, your spine and rib cage subtly rise and settle on the wave of your breathing. Breathing is easy and pleasurable. As the song goes, “Easy like Sunday morning.”

What do you sense in your own body as you look at the photo on the facing page? As you gaze at the woman in the desert scene, imagine yourself in a similar environment, surrounded by open space. Imagine allowing your arms to swing upward as if to embrace that space. It is almost certain that your gesture will be accompanied by inhalation. In fact, if you try making the same gesture while exhaling, you will probably find that it feels awkward.

Now imagine resting into the earth like the person on the beach. Or picture yourself relaxing on a chaise lounge by a pool at your favorite resort. Let your body yield into the support of chaise and earth. Notice that the more completely you can enter this image of relaxation, the slower, steadier, and lower in your lungs your breathing becomes.

While inhalation lifts and tones the body, exhalation settles it. Just as our perceptions of spaciousness and weight contribute to the optimal organization of the muscles of posture, these same perceptions contribute to healthy breathing.

Breathing Meditation

The following practice helps you balance the motions of breathing by attending to their spaciousness and weight. To do the exercise, you need to be lying down in a position that supports openness through the rib cage.

As you inhale, allow yourself to welcome the air into your body. Feel the subtle expansion of your entire skin surface as the ribs expand. Imagine your pores are also absorbing oxygen. Imagine being on a mountaintop, breathing in the pleasure of the scene. Tune in to your gratitude for each breath. This deep breathing should be accomplished without strain in your natural rhythm. If you find that spacious inhalations become taxing, alternate them with one or two ordinary breathing cycles. Notice any tendency to pull or suck the air inside. Should you feel yourself doing that, forget about the inhalation practice for now and go on to the exhalation practice.

During your exhalations, shift your attention away from the expelling of air. Focus, instead, on surrendering your body to gravity. For your exhalation to be complete, your body must relax—every muscle, organ, and bone. It will be helpful to sense your body’s weight in stages. During several exhalations, focus on surrendering the weight of your legs. When your legs feel truly heavy, shift your attention to your abdomen, and then to your spine, belly, hands, or eyes. Scan your body for regions where you seem to be held up from the ground. Then allow that part to sink.

As you relax, you will find yourself automatically exhaling more slowly and deeply. You will also notice a pause occurring after each exhalation. This respiratory pause is a needed moment of rest for your hard-working diaphragm muscle. The pause also allows time for your autonomic nervous system to respond to the oxygen/carbon dioxide balance of your blood. Your blood chemistry signals the breathing center in your brain that you need more oxygen. Because your inhalation is automatic, it feels effortless.

Practice this breathing exercise for at least five minutes every day. In time, your increasingly slower and longer exhalations will lead to increasingly effortless and expansive inhalations. End each breathing session with a few moments’ awareness of your body’s length and openness. Imagine yourself standing upright and retaining these sensations of spaciousness and weight. Imagine yourself walking across the room that way. Finally, stand and experience the actual shift in your posture.

Besides having an effect on your posture, the breathing meditation can provide opportunity for self-study. Within your breathing cycle, you embody your habits of receptivity and surrender—the ways in which you let experiences in and how you let them go. Notice whether you receive your inhalation with urgency, trepidation, or with a sense of gratitude. Notice whether you exhale with reluctance, relief, or surrender. Notice how comfortable you are with the emptiness of your respiratory pause.

Facilitating Clients’ Breathing Awareness

In the high pressure environment of the twenty-first century workplace, many people’s perceptions become so overwhelmed that the dynamic orienting and stabilizing process described earlier cannot occur. Instead, people’s bodies become habituated to a constant state of low-grade global tension and unconscious breath-holding that, in turn, perpetuates chronic tension.

Holding the breath in creates pressure in the abdomen that makes the trunk feel stable. Holding the breath out necessitates tension in the abdominal muscles that also accomplishes a feeling of stability. For some people, holding the breath seems to serve as a way of gaining control over time. Without the regular ebb and flow of breathing, there is an illusion that time has stopped, prolonging the arrival of a deadline.

As your clients relax, their slow, regular breathing is, for many of them, the most complete breathing they do all week. And most, if you introduce the topic of breathing, will say immediately, “I know I don’t breathe right.” While not all clients are open to self-care, most are grateful for any advice you can offer. For many, their massage therapist or bodyworker is the only person they can freely talk to about their bodies. While you cannot give detailed breathing instruction during a massage, you can invite breathing awareness.

Your goal is simply to help the client learn to duplicate the relaxed steady breathing that occurs during a massage. After a client has admitted that breathing is a problem, make a contract to spend some time on breathing awareness during the next treatment. What you will be doing is gently leading your client through the breathing meditation described in the previous section. Draw your client’s attention to how she is breathing at the beginning of the session. Invite her to notice the relative ease or difficulty of inhalation or exhalation. Ask whether it feels more pleasurable to breathe in or breathe out. Such questions help the client identify her breathing habits so she can more easily appreciate change when it occurs.

Ask her to notice the subtle pause at the end of exhalation. For a client whose breathing is excessively shallow and rapid, the pause does not occur. In such a case, do not encourage the client to force the breath to stop after exhalation. As she relaxes more completely, the pause will naturally emerge.

As your work progresses and the client’s breathing slows, invite her to attend to the increasing heaviness of different areas of her body. Most people do not associate relaxation with the sensation of weight. But the more they learn to feel and appreciate that sensation, the more easily they can achieve relaxation. As your client’s body settles, point out to her that her breathing has also become slower and deeper.

If your client seems to need help expanding the rib cage for inhalation, ask her to describe a peaceful scene in nature, her favorite mountain vista, or shoreline view. By imagining space, she automatically inhales more freely.

Breathing Awareness While We Work

The environment in which we work affects our breathing, our body use, and, ultimately, our posture. Many treatment rooms are small and have dim lighting. While this ambiance conveys peace and safety for a client, the confined space tends to draw the therapist’s own body down and in. As we bend over the table, our work often rounds the shoulders, compressing the rib cage and restricting breathing. Our attention on the client can also distance us from our own sense of space. A loss of spaciousness both restricts breathing and contributes to poor body use. So, at the end of the day, we are the ones needing a massage.

If you resonate with this description of a therapist at work, you can begin to change the picture by practicing the breathing meditation outlined in this article. If you are in the habit of centering yourself before you begin a massage, incorporate your new sense memories of spaciousness and weight into that centering meditation. Then, as you work, maintain a small part of your awareness on your perceptions. Remind yourself often to expand your sense of space beyond the confines of the small room. Feel the weight of your body resting into your feet and your feet resting into the floor. By letting your awareness play with these sensations, you are giving your nervous system the information it needs to organize your body better.

You can give full attention to your client and still keep 10 percent of your awareness on your own comfort. This strategy will actually improve your touch, because the more at ease and comfortable you are, the better your touch will feel to the client. This only makes sense because, in the holistic world of your treatment room, everything is connected. How you touch emerges out of how you perceive yourself in the situation—how you “put yourself” in relation to your client and to the giving of service.

Mary Bond teaches at National Holistic Institute in Los Angeles and is on the Movement Faculty of the Rolf Institute. She is the author of Balancing Your Body. Her new book, The New Rules of Posture: How to Sit, Stand, and Move in the Modern World, is available through Healing Arts Press. Visit her website at www.newrulesofposture.com.

Notes

1. Mary Bond, “Posture and the Perineum,” Massage & Bodywork, October/November 2006, page 18.

2. Most clients are not well informed about how the body works; therefore, the term abdominal breathing leads them to think that respiration takes place in the belly. It is a service to clients to educate them about how breathing actually occurs. Just a few anatomical details can ground and inspire their attempts at correcting poor breathing habits.

3. I am indebted to movement educator Hubert Godard for the understanding of the relationship between posture and perception. Because of space limitations, the topic has only been touched on here. For more information, see my book, The New Rules of Posture: How to Sit, Stand and Move in the Modern World (Healing Arts Press, 2006).