Anyone who performs bodywork has encountered this situation at one time or another: the client presents with an episode of sharp, severe, low back pain. There may be a history of pain with lifting or prolonged sitting and the pain is usually greater on one side more than the other. The pain may radiate into the buttocks and sacrum and perhaps to the lateral thigh and into the lower extremity. The pain may worsen with extended sitting and with any forward flexion of the spine.

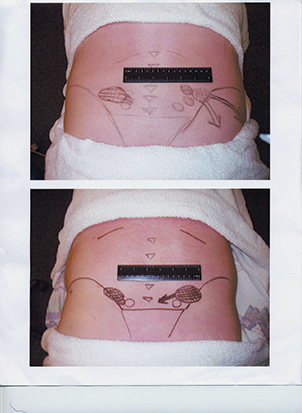

The back mouse is one or more firm, mobile 1.3 cm nodules that trigger back and sciatic pain when pressed. Photos courtesy W. David Bond.

Medications may not be helpful and the client is usually unable to find a comfortable position. The client has tried everything, been everywhere and you are his last hope. When asked to point to the area of the greatest pain, he will invariably point just above and lateral to the natural “dimple” where the back and buttocks come together, near the multifidis triangle. When that area is palpated, the most marked finding is one or several firm, mobile 1.3 cm nodules that, when pressed, reproduce the client’s complaints of back pain as well as the “sciatic” pain. The photos below map the location on two clients. Clients often exclaim, “That’s it. That’s where all my pain comes from!” You have just found the elusive “back mouse.”

A Sensitive History

The term “back mouse” is a rather cute description for a very painful yet often overlooked problem, even by back pain specialists. Originally termed the “episacroiliac lipoma” by E. Ries in 1937,1 it was later labeled the “back mouse” by Peter Curtis in 1993.2

I first encountered the back mouse while learning various soft tissue techniques in chiropractic school. While palpating over the sacral region, I would feel these small, firm, fleshy yet moveable nodules. Firm pressure directly on the nodules would produce pain and tenderness, as well as local radiation into the sacrum and hip. Thinking that they were trigger point nodules, I would apply direct and deep ischemic compression, which only served to aggravate any pain. This however did not dissuade me from applying deeper pressure, as this was most certainly not bone and we were taught to apply trigger point therapy to soft tissue nodules. They appeared to be definite, moveable and encapsulated masses much like a subcutaneous lipoma and not at all like a band of skeletal muscle. Further-more, I had encountered many subcutaneous lipomas in the back region and they were always the same: moveable, non-tender “speed bumps” that caused pain only when they compress the underlying soft tissue.

Subcutaneous lipomas are found all around the body, grow slowly over time and are only cosmetically important. The back mouse, though, is only found around the sacral region and is generally tender and at times painful. Also, the back mouse seems to suddenly appear following trauma to the back as in motor vehicle accidents or perhaps following a lifting injury.3 The size of the nodules does not change and they remain the same regardless of the administered soft tissue treatment, so they couldn’t be muscular. But why would a lipoma be both tender and predictable in location?

Image 1. Lumbar subfascial fat layer.

Perhaps a more descriptive term than the back mouse is actually that of the “lumbar fascial fat herniation” as described by W. S. C. Copeman and W. L. Ackerman.4 Some other terms are: Episacral lipoma, iliac crest pain syndrome5 and multifidus triangle syndrome.6 A lumbar fascial fat herniation occurs when the lumbar subfascial fat layer (see Image 1) herniates through the overlying thoraco-dorsal fascia (see Image 2) and gets trapped and inflamed. The mechanism appears to be due to an anatomical defect or weakened area in the fascia, which, when there is increased internal pressure, allows the fat lobules to push through the fascia.7 Once herniated, the fat becomes trapped and as an expanded, inflamed, herniation in an otherwise unyielding fibrous capsule, this creates a focus of pain. Pressure on the lipoma does not push it back through to fascia but only inflames the torn fascia more. These herniations occur at predictable sites along the iliac crest and sacrum very close to the natural dimple area (see Image 3). They also are approximately three times more prevalent in women, particularly in moderately obese women.8

Image 2. Overlying thoraco-dorsal fascia.

Over the years I have also encountered many episacral lipomas and I am always amazed at the strength of the positive “doorbell” sign. It is a reliable sign in that firm pressure usually reproduces the exact complaint that the client relates in their symptomatology. Direct pressure even reproduces the sciatic or radicular-type pain without any stretching of the sciatic nerve and without any motion to the lumbar facet or sacro-iliac joints. In this respect, it is similar to the active trigger point with a zone of referral. But if it is not purely a muscle problem, nor joint, nor nerve, then how do you conquer the back mouse?

Image 3. Iliac crest and sacrum.

Cycle of Pain

Unfortunately, typical “back mouse” clients have usually run the gamut of treatment protocols. They have seen and have had evaluations by multiple specialists including acupuncture, chiropractic, orthopedic, neurological, psychological, etc. They have perhaps been diagnosed as having myofascial pain syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain strain or fibrositis as well as arthritis, disc herniations, etc. They may have had radiographs, MRI studies or nerve conduction studies, all with usually negative or minimal findings. Or they may have a minor disc bulge without nerve compression, yet the pain exactly mimics a disc herniation.

There appears to be a focus by back pain specialists upon the disc and nerves even though these lipomas are readily palpable. Many have had epidural injections without success. I have had clients who have had surgery for disc herniations yet who still point to the back mouse as a large percentage of the post-surgical pain. It is perhaps considered diagnostic for the presence of a lumbar fascial fat herniation if a local infiltration of anesthetic takes away the pain. But many clients do not want to pay the $150 or so for a few hours relief. Many have gone through the pain pill merry-go-round, taking a cocktail of pain and anti-inflammatory medications even though the pain never truly goes away. There is a wealth of information to be gained through digital palpation, something at which massage and bodyworkers usually excel. A client with excruciating low back pain, the presence of the back mouse and pain reproduced at the site of the lipoma should lead the practitioner toward manual soft tissue therapy for a lumbar fascial fat herniation unless proven otherwise.

Avenues of Relief

If the back mouse fails to respond to conservative treatment, I recommend the client see his primary care physician, chiropractor or acupuncturist, and request further evaluation. A medical doctor can inject the back mouse with a local anesthetic, which may help temporarily. Dry needling techniques by acupuncturists may help reduce the tension in the fibrous capsule. Excellent results also may be obtained with local electrical stimulation. Perhaps the only permanent cure for the back mouse is its excision and removal. Those patients who are at the end of their proverbial rope, I send to a hernia repair specialist. Once the fat herniation is excised, the fascial tear is repaired and the client enjoys a more enduring and sometimes dramatic relief. One problem is that so many medical doctors fail to recognize this condition; they tend to discount its existence thereby limiting the treatment options.

The back mouse is a fairly common problem, which on first view may have a symptomatology similar to a disc herniation. It can be responsible for a significant degree of low back pain that’s absent from positive diagnostic studies. The considerable level of pain may at first be daunting for the bodyworker. However, if the practitioner first recognizes the existence of a fascial fat herniation, palpation confirms the condition. Conservative treatment geared toward pain relief and treating the fascial tear rather than trigger point therapy on an inflamed, herniated and edematous fat lobule is most helpful. Changes in lifestyle and exercise may help to further alleviate the condition, and other treatment options are always available should the back mouse present itself.

Soothing the Back Mouse

For the past 10 years, I have been an advanced course instructor for the palpation and biomechanics classes at the Touch Therapy Massage Institute. In each class of 20 to 22 students, we find at least two to four individuals with tender episacral lipomas. I tell them that when I have a client with an obvious back mouse, I apply the following rules:

Do not apply deep pressure.

Doing so may only serve to aggravate the herniation. Deep pressure may and should be applied to the surrounding paraspinal and hip musculature (as client comfort will allow), but avoid applying pressure directly on the lipoma. Since it is a fascial problem, I apply a fascial stretch to the thoraco-dorsal fascia. I apply trigger point therapy to the surrounding musculature and a sports massage to the low back, again excluding the lipoma itself.

Do not stretch the low back.

Many clients feel they should stretch the low back, usually by touching their toes or by twisting. It is through an inherent fascial weakness or faulty biomechanics that this problem evolved and when the client puts additional pressure on the fibrous capsule, the inflammation may worsen. I do recommend stretching when the back pain improves above a 50 percent level, but not before. When stretching the hamstrings, I always have the client standing with the leg elevated on a chair, or something of waist height.

Do not suggest exercise.

Exercise tends to aggravate the problem at least until the client improves above the 50 percent pain level. Many clients I see actually aggravate the back mouse while doing some kind of exercise. They have the misconception that painful soft tissue needs exercise so they tend to overdo it. As they improve through treatment, some mild exercise should be added. I recommend tai chi, qigong or swimming as the best exercises for someone with a back mouse.

Apply ice.

Since the back mouse results in inflammation, ice will tend to sedate the nerves and cool the heat. After a treatment, I tell the client to go home and apply ice for a few minutes at a time. As he improves, I tell him to start using heat as long as he does not fall asleep on the heating pad.

Avoid lying on a hard surface.

Some clients have heard that for back pain, they should lie on a hard surface. This may be true for some conditions, but not for the back mouse. The pressure on the capsule may aggravate the condition and cause further inflammation.

Avoid prolonged sitting.

Prolonged sitting and/or prolonged driving tends to aggravate the condition first by direct compression of the lipoma and then by deconditioning of the low back. The hamstrings tend to tighten and the abdominal muscles weaken. This will cause the low back musculature to tighten, further putting pressure on the fascia. If the client spends hours in traffic, a low back support pillow or rolled-up towel is helpful.

W. David Bond is a chiropractor practicing in Southern California. He specializes in the treatment of acute, chronic and myofascial pain. He received his doctorate in chiropractic from the Los Angeles College of Chiropractic in 1987. He is a licensed Qualified Medical Evaluator for the state of California and is a diplomate in pain management by the American Academy of Pain Management. He has taught advanced massage and palpation techniques at the Touch Therapy Massage Institute since 1993, and is the founder and clinic director of the Essential Chiropractic Center in Encino, Calif. He can be reached at zonte@sbcglobal.net.

References

1. Ries, E. Episacraliliac Lipoma. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1937, 34:490.

2. Curtis, Peter. In search of the back mouse. Journal of Family Practitioners. 1993, Jun; 36(6): 657-9.

3. Copeman, W.S.C., and Ackerman, W.L. Edema or herniations of fat lobules as a cause of lumbar and gluteal fibrositis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 79:22, 1947.

4. Copeman, W.S.C., and Ackerman, W.L. Fibrositis of the Back. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 1944; 13:37-51.

5. Collee, G., Dijkmans, B.A.C., Vandenbroucke, J.P., Cats, A. Iliac crest pain syndrome in low back pain: Frequency and features. Journal of Rheumatology. 1991;18(7):1060-3.

6. Bauwens, P. and Coyer, A. The multifidis triangle syndrome as a cause of low back pain. British Medical Journal, Nov. 1955, 1306-7.

7. Singewald, M. Sacroiliac lipimata — an often-unrecognized cause of low back pain. Bull. John Hopkins Hospital. 118:492-498, 1966.

8. Pace, J. Episacroiliac lipoma. American Family Physician. 1972, Sept., 70-3.