By Ruth Werner

Originally published in Massage & Bodywork magazine, April/May 2006.

Nearly 40 million people in the United States received a professional massage in 2005. What are the chances all of them were healthy and problem free? Slim to none, of course. People seek massage for more than the occasional indulgence. Massage is used increasingly for pain management, injury repair for trauma, speeding recovery time for athletes in training, or enhanced quality of life for those who simply want to live at the peak of their physical capacity.

As massage therapy moves from the fringes into the mainstream of first-choice coping mechanisms, practitioners must face a number of challenges. We must weigh the benefits and risks of massage for people with complex health conditions; we need to stay on top of the latest and most effective techniques; and we must follow the exciting advances in massage research. Therapists today must achieve a higher level of education and preparation than ever before, even to work in settings geared more to relaxation and recreation than to clinically measurable outcomes.

There was a time when a perceived schism appeared in the world of bodywork: Some practitioners saw themselves specifically doing relaxation massage, while others aimed for rehabilitative goals. In some parts of the country, this rift is still significant. But I would like to suggest just as the body and the mind are not two separate entities, relaxation massage and clinical massage are likewise inextricably bound. And while some therapists may aim for working only in recreational settings, this does not remove the responsibility to be knowledgeable about the many physical challenges clients at a high-quality spa may present. Those decisions begin, of course, with the all-important client intake conversation.

Even in the olden days of massage education (i.e., way back when I was in massage school), when we interviewed a new client, we were instructed to ask, “Are you taking any medication?” We had little knowledge, however, of what to do with that information. Today, that question is more important than ever, because more Americans who take medication on an ongoing basis may seek massage. While in most cases bodywork is unlikely to cause an adverse effect, it is important to be familiar with the basic mechanisms of some medications and their possible side effects.

Let’s focus on a few of the medications many of our clients take regularly and how they may impact decisions about bodywork. At the outset, it is important to make clear the relationship between massage and medications is understudied, to say the least. The following information is gleaned from a few sources, listed at the end of this article. In light of the fact that more Americans than ever are on long-term medication courses, it is clear every massage therapist should keep at least one good pharmacology book close at hand. Clients don’t always understand the purpose or mechanism of the medications they have been prescribed, and you never know when someone will write “Zestril” in the medication entry on an intake form.

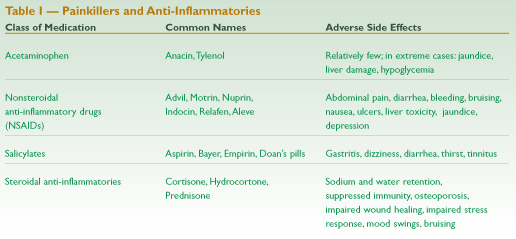

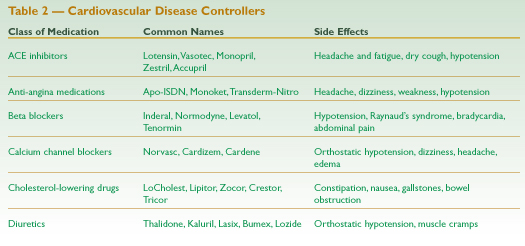

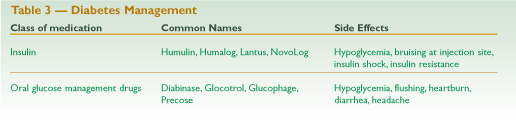

Some of the most common drugs massage therapists may encounter include painkillers and anti-inflammatories, medications to control heart disease, and drugs to manage diabetes. Some common brand names have been provided, but this information is always in flux — another reason to own a good pharmacology book.

Painkillers and Anti-Inflammatories

Many painkillers work to dull sensation by reducing or inhibiting the inflammatory process (see Table 1). Other analgesics alter pain perception in the central nervous system and do not affect inflammation. Regardless of the site of drug activity, painkillers and anti-inflammatories change tissue response. It is important to work conservatively with clients who take these medications, because information we gather about temperature, muscle guarding, local blood flow, and other signs will be altered, and overtreatment is a significant risk.

Although it is inappropriate to suggest clients skip or change their medication for massage, it is preferable to work with clients when these drugs are at their lowest level of activity (toward the end of the dosage period) so therapists may collect the most accurate information about tissue response.

Cardiovascular Disease Controllers

Cardiovascular disease causes nearly 40 percent of U.S. deaths. And heart attacks are the leading cause of death in this country, claiming more than 500,000 lives each year (that’s more than 1,300 people every day).1 Since approximately 50 million people have high blood pressure,2 it is reasonable to assume some of them will seek massage, so practitioners should be familiar with the most common cardiovascular medications (see Table 2, page 124).

Most of the drugs used to treat cardiovascular disease work in some way to minimize the sympathetic response, to dilate peripheral blood vessels, or to promote increased urination. When a person uses these substances, her slide into a parasympathetic state may be intensified by massage, leaving her dizzy, fatigued, and lethargic. Ending a session with more stimulating strokes may help to balance these effects, as long as they fit into a protocol suitable for a person with compromised cardiovascular health. Clients should be instructed to sit up and move slowly after their massage, in order to minimize dizziness or discomfort. Some experts suggest the massage therapist stay with the client until she is sitting up and no longer dizzy.

Some cholesterol-lowering drugs increase the risk for constipation, which indicates massage, but they can also cause gallstones or bowel obstruction, which requires immediate medical intervention.

Diuretics may cause muscle cramps through the loss of key electrolytes (this drug choice should be pursued with a doctor rather than a massage therapist).

Hydrotherapy applications can challenge the ability to maintain homeostasis more than other modalities. Many clients with cardiovascular diseases should avoid total immersions in favor of more localized hydrotherapy applications.

Diabetes Management

Nearly 18 million people in the United States have type 2 diabetes. When this disease cannot be managed by diet and exercise alone, other interventions are used, including glucose management drugs and the supplementation of insulin in various forms.

The implications of massaging a diabetic client can be significant. While many diabetics manage their disease well and minimize their risk for secondary complications, others are prone to several problems that pose serious cautions: systemic atherosclerosis, an increased risk of stroke, diabetic ulcers, and peripheral neuritis, to name a few.

Furthermore, massage lowers blood glucose. While this is an advantage to diabetic clients, this challenge to homeostasis on top of their medications may be enough to trigger a hypoglycemic episode. Massage therapists with diabetic clients should be aware of signs of hypo- and hyperglycemia and should consult with those clients about how best to address their needs in an emergency.

Diabetes drugs affect blood sugar in both the short and long run (see Table 3). It is important to have as little impact on this process as possible. Therefore, massage for a diabetic client should typically be conducted in the middle of a dose’s activity, rather than at the beginning or end of the drug’s effect. Injection sites or insulin pumps should be locally avoided for the same reason. Clients new to massage might choose to check their blood glucose at the beginning or end of a session in order to determine whether they should eat first. Therapists with diabetic clients might choose to keep a high-sugar snack handy (milk, candy, juice) in case they experience a hypoglycemic episode.

***

What we have covered here is only a tiny sampling of the thousands of medications Americans take on a regular basis. Antidepressants, antianxiety drugs, attention deficit and hyperactivity drugs, antibiotics, thyroid supplements, asthma controllers, hormone replacement therapy, and anticancer drugs are among the long list of medications our clients may use. The world of pharmacology in the context of massage is largely unexplored territory. It is my hope the many branches of research into the physiological effects of massage will continue to explore this topic and reveal more ways for massage therapists to minimize the risks of their work while maximizing the benefits.